They say the people of Val Venosta have hospitality in their blood. Sounds like marketing talk at first – but it isn’t. It’s more of a belief, rooted as deeply as the apple trees in the valley. And since we in Val Venosta like to back things up with proof, we take a closer look – with a pinch of philosophy, a few historical facts, and the right dose of humor. After all, we want to know what really runs through the veins of the Vinschger people.

Here’s a bold starting point with two theses: the roots of Val Venosta’s hospitality lie, on the one hand, in the valley’s unique position as a passageway, and on the other, in the living conditions that have shaped its people over centuries.

Val Venosta – a Valley of Passage

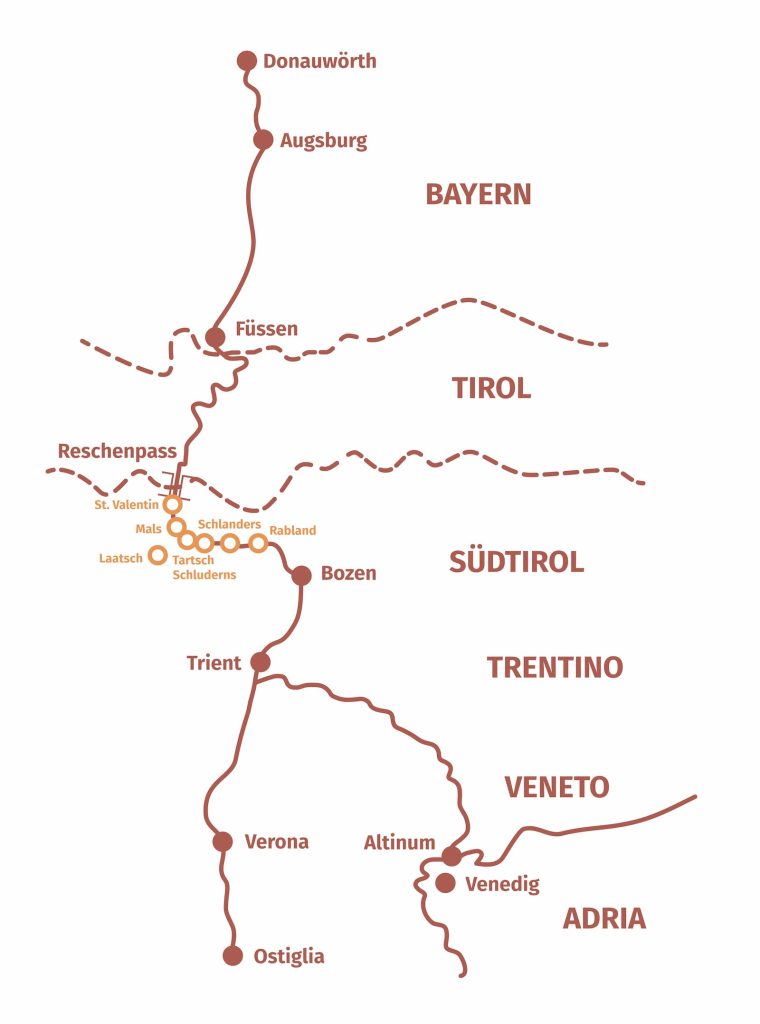

Around 15 BC, things started to get interesting here in Val Venosta. Drusus, stepson of Emperor Augustus and commander of the Roman troops, carved a path through the valley and over the Reschen Pass. By doing so, he opened the door for the Roman Empire to expand into the northern Alpine regions.

That first connection was later transformed under Emperor Claudius into the legendary Via Claudia Augusta – a road that stretched from Verona, through Val Venosta, all the way to Donauwörth near Augsburg.

More than 560 kilometers long, this ancient highway became a lifeline for trade, military movements, and cultural exchange across the Roman Empire.

All Roads Lead to Rome

Today, the Via Claudia Augusta is one of Europe’s most famous long-distance routes – both for hikers and cyclists.

Many who travel along it stop by the FinKa in Mals (

And while the FinKa didn’t exist back then, Mals was already right in the middle of it all.

The town sat like a hinge between north and south, east and west. Here, the great north–south axis crossed the route to Chur and the western Alps. No wonder Mals became a lively settlement area: the Romans even built a mansio – a roadside station for soldiers, merchants, and later pilgrims. It offered a place to rest, eat, and – quite naturally – catch up on the latest news from the world.

In short: Mals was already, 2,000 years ago, a cosmopolitan meeting point – a crossroads where paths met, goods changed hands, and stories were traded.

For centuries, travelers passed through the valley, and Mals remained the hub between all directions. Or, with a wink: that old saying “All roads lead to Rome” might well be expanded to “…and quite a few of them led through Mals.”

Even after the fall of the Roman Empire, the great trade routes remained.

The Roman settlements and mansiones slowly turned into medieval inns and taverns – places where merchants and pilgrims found shelter. Markets sprang up – not just trading posts for goods, but lively spaces of social exchange.

Thus, a tradition of hospitality developed early on: doors were open to travelers, and the people of Val Venosta learned to adapt again and again to the changing needs of those who passed through.

Hard Living and the Experience of Being a Stranger

Hospitality in Val Venosta did not arise merely from geography.

It also grew out of the hard living conditions up here – and from the very human experience of being a stranger oneself.

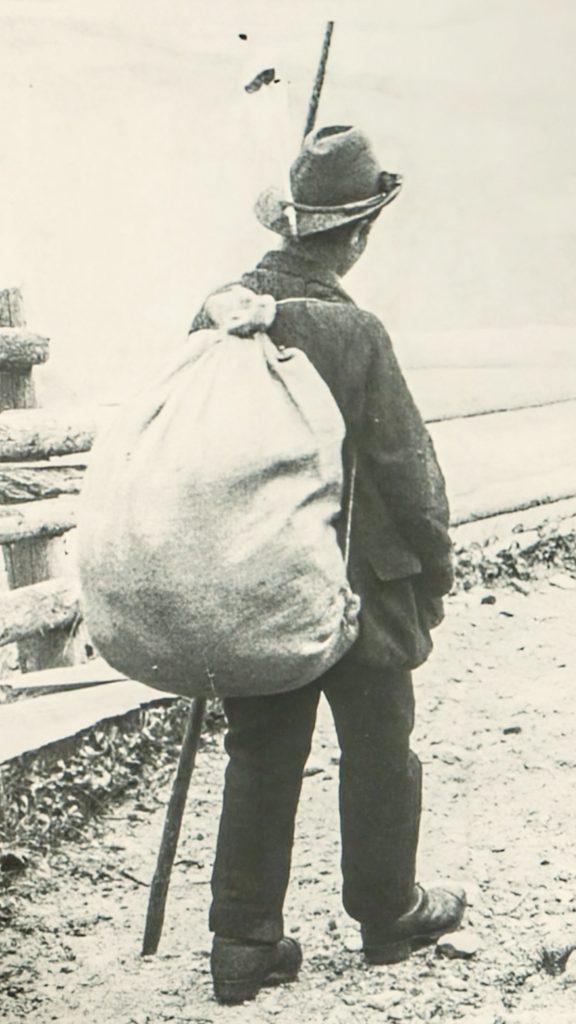

The mountains offered protection, but they also isolated. The soil was meagre, summers hot, winters long and icy, and the wind often merciless. Little more than rye, barley, and a few potatoes would grow. Through the division of inheritance, land shrank generation by generation until it could no longer feed the families. Those who had nothing left packed their few belongings onto a cart and took to the road as Korrner – itinerant craftsmen, knife-grinders, broom-binders, tinkers. They were seldom welcomed, but always needed. People offered them a bowl of soup or a corner to sleep in – perhaps out of compassion, perhaps from that quiet awareness: it could just as easily have been us.

Equally harsh was the fate of the Schwabenkinder – the “Swabian children.” Every spring, hundreds of them crossed the Alps on foot to Upper Swabia, where they were hired out as cheap farm labour on so-called child markets.

For the families in the valley, those few earned coins meant survival. For the children, it meant hard labour, hunger, and homesickness. Many returned marked for life – grown up too soon, often inwardly estranged.

The story of working away from home continued into the twentieth century. After the war, young women from Val Venosta went to the cities of northern Italy or to Switzerland to work as maids and housekeepers. They sent money home – and brought something valuable back: the ability to host guests, to run a household, to sense people’s needs. These skills would later shape the birth of tourism in the valley.

After the hardship of the inter-war years and the horror of the Second World War, the 1950s and 1960s brought a wave of visitors. Tourism became the main source of income for many families. Simple guest rooms – the so-called Fremdenzimmer – appeared in farmhouses and village inns, offering travellers plain but genuine accommodation in a homely atmosphere.

All this left deep traces in the collective memory: those who had once been strangers themselves knew how vital it is to feel welcome when far from home. Perhaps that explains why the people of Val Venosta still have such an instinctive sense for hospitality.

From Vinschger Hospitality to FinKa Hospitality

Two things define hospitality in Val Venosta: centuries of practice in welcoming travellers – who brought not only income but also stories and new ideas into the valley – and the lived experience of displacement, of knowing what it means to be a stranger. This double experience is deeply rooted in the valley’s cultural memory and continues to shape the way people here open their doors to others.

That’s precisely where we at the FinKa pick up the thread. How could we not? We carry this cultural heritage within us. But we choose to live it in our own way – inspired by the old principle of the inn and the Fremdenzimmer: places that are simple, open, and honest. Places where you arrive without fanfare and yet remember long after you’ve left.

So we designed the FinKa as a counterpoint to standardized hotels and package tourism. With quiet corners and lively meeting points, a self-catering kitchen and our Trattoria Evenings, a small library in the Salone, an old bathtub in the garden, and a bench for anyone who feels like looking out over the valley and thinking about life, the world, or nothing at all.

The idea behind it is simple: hospitality should feel free. No one has to consume, everyone may. Bring your own beer from the supermarket if you like. Sit down with us for Knödel or pizza if you feel like company – and share a story.

In short: we wanted to turn Vinschger hospitality into our own kind of FinKa-style guest culture – honest, grounded, and just a little out of time.

Such places are what we’re always looking for when we travel – and so rarely find. Simple places that, through small details and a sense for atmosphere, make a stay feel timeless and genuine. That’s exactly what we’ve worked toward. Our wish – then and now – is to make the FinKa such a place, one that’s woven into its surroundings, its culture, and its history.

Side Glances

Leo’s Knödel Art

Anyone coming to the FinKa should definitely try Leo’s Knödel – his speck and cheese dumplings are a straight path to culinary heaven. It’s a kind of ritual: the way he prepares them, with such care, the way he mixes and shapes the ingredients until they reach that perfect rouglige (fluffy-light) consistency – it’s an art form of its own.

The Strict Secret of the Nonna

Our pizza has long since achieved cult status. It’s made according to an old southern Italian family recipe using Lievito Madre – natural yeast. We owe that recipe to a nonna from Basilicata. In the first year of the FinKa (2021), a group of Italian construction workers stayed with us. When they saw our pizza oven, one of them immediately called his grandmother. She dictated her recipe over the phone – but only on one condition: that we swear by the Holy Virgin Mary never to share it. Since then, we’ve guarded that secret like a treasure.

Living-Room Concerts and the Festival

The FinKa is not just a hostel – it’s also a stage. Every now and then our Spaccio (dining room) turns into a living room for intimate concerts. On those evenings, there’s music, laughter, sometimes deep conversation, and often jam sessions that stretch far into the night. From these small gatherings, a tradition was born – the FinKa Festival, now a November fixture that brings together singer-songwriters and guests to eat, drink, and celebrate.

The smallest festival in South Tyrol – and perhaps the most heartfelt.

Unexpected Encounters

Maybe the most magical thing about the FinKa is that you never know who will walk through the door next.

Cyclists heading for the Stelvio Pass. Hikers following the ancient Roman Via Claudia Augusta. Adventurers crossing half the world on their bikes – sometimes only stopping once they reach the Great Wall of China.

Nobles and journeymen, artists and architects – drawn here, perhaps, by word of Esther Stocker’s artwork that adorns our lift shaft.

That’s the FinKa’s flair: it brings together people who might never have met otherwise.

And sometimes, all it takes is one shared evening – with Knödel, pizza, or music – to create stories that linger long after.

What the FinKa Stands For

In the end, it’s quite simple: the FinKa is a place where hospitality stays alive – with Knödel and pizza, with concerts and festivals, with encounters you can’t plan. A house that beats to its own rhythm – honest, down-to-earth, free.

Those who come here should feel at home – no pretence, no pressure, just the freedom to bring their own stories.

Maybe as a cyclist on the Via Claudia Augusta, as a musician at the living-room festival, or simply as a traveller with a book in their backpack.

Because that’s what makes the FinKa what it is: a place that’s not just accommodation – it’s memory.

In Short

Hospitality in the blood: from the Romans to the FinKa – Knödel, pizza, living-room concerts, and the kind of stories that stay with you.

Hospitality in Val Venosta runs deep. It grew from the valley’s role as a crossroads and from the hard experience of being a stranger oneself. From Roman road stations to wandering craftsmen and Schwabenkinder, right up to the post-war tourism boom – hospitality has always been part of the valley’s way of survival.

The FinKa carries that heritage forward – but in its own way. Not as a hotel, but as a hostel with soul: Knödel and pizza, living-room concerts, the November FinKa Festival, a library, an old bathtub in the garden – and above all, encounters you can’t plan.

The FinKa is a place where hospitality continues to breathe: honest, grounded, free – and always a little out of time.

Since when has hospitality existed in Val Venosta?

Its roots reach back to Roman times. With the construction of the Via Claudia Augusta (15 BC under Drusus, later expanded by Emperor Claudius), Val Venosta became a vital north–south connection. Even then there were roadside stations (mansiones) offering travellers rest and supplies.

Why was Mals so important in Roman times?

Mals was strategically located. The Reschen Pass was relatively low and the valley rose gently northward.

Trade routes met here – north, south, and west. Archaeological finds still show Roman settlements and road stations around Mals.

Who were the “Korrner”?

Korrner were poor Vinschger who travelled the land as wandering craftsmen – knife-grinders, broom-binders, tin-menders. They weren’t highly regarded, but they were welcomed because their work was needed.

What were the “Swabian Children”?

From the 17th century on, poor families sent their children across the Alps to Upper Swabia, where they were hired out as cheap farmhands at child markets. For the families the money meant survival; for the children it meant hardship, deprivation, and homesickness.

How did labour migration shape hospitality?

After WWII many young women from Val Venosta worked as maids in Italian cities or in Switzerland.

They returned not only with savings but with something lasting – an intuitive feel for guests, homes, and service – skills that later shaped the region’s tourism.

What makes the FinKa special today?

We carry that tradition forward – but freely. The FinKa is intentionally simple: a self-catering kitchen, Knödel and pizza evenings, living-room concerts, and our tiny November festival. Hospitality here means freedom, authenticity, and encounter.

Who is the FinKa for?

For everyone: cyclists on the Via Claudia Augusta, families, solo travellers, groups, and culture lovers – anyone looking for something more than just another hotel bed.

Experience the FinKa

📩 Bookings & Reservations:

info@finka.it

📞 Phone: +39 0473 427040

🌐 www.finka.it

Sources:

Historic Via Claudia Augusta

https://www.uibk.ac.at/archive/

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Via_Claudia_Augusta

https://www.vuseum.it/roemer

The Modern Hiking and Cycling Route – Via Claudia Augusta

https://www.viaclaudia.org/geschichten/via-claudia-augusta-geschichten

Swabian Children

https://www.vuseum.it/schwabenkinder

Korrner

0 Comments